Stage fright has been part of my life for as long as I can remember.

Stage fright has been part of my life for as long as I can remember.

It’s very selective.

I’m fine in front of a crowd of thousands, especially in halls where the lights are on me and I can’t see the faces of anyone past the first row or two… and even they are too dark to see clearly.

Put me in front of an audience of 20 or 30 people, where I can see every face and every micro-reaction to what I’m saying…?

Panic.

Total panic.

I have to steel myself to even think about that kind of public speaking.

That’s why, when I teach, I have a firm rule: I need access to the classroom, in solitude, for at least 30 minutes before the students arrive. (Otherwise, I’m likely to blurt all kinds of things… usually extreme and unexpected. It can be confusing if you’re not ready for the panalopy of creative ideas that rush through my mind. The words can tumble out, sometimes a little scrambled, like high schoolers rushing to class before the “late” bell rings.)

During my personal pre-class time, I give myself a “pep talk,” and use breathing techniques that would make Dr. Lamaze proud, to relax myself enough to teach. With the right mindset – or at least mental distance from “not good enough” self-talk – I can teach a great class with lots of student involvement.

(Without exception, every class I’ve taught that fell flat… it’s because I wasn’t given that 30 minutes to prepare.)

Creating art can be a similar issue for me and many other people. We may not have that visible audience, but when the initial spark of inspiration fades, the voice of the inner critic can be worse than any heckler in the classroom.

(You know that student. She’s the one who sighs loudly and repeatedly. And, at the end of the class – when it’s too late to do anything about it -she tells you how deeply you’ve disappointed her, and how you really shouldn’t be teaching. Or making art. Or both.)

Regardless of where the message comes from, we’re often striving for impossible perfection… as artists and as teachers. The slightest shortfall or flaw seems magnified on a big screen and in HD, and every metaphorical pore and blemish is the size of the Grand Canyon.

In fact, we’re often our very worst critics. We hold ourselves up to impossible standards, and we’re usually using the wrong measuring stick.

Last night, I was disgruntled. I’ve been working on a series of small (5″ x 7″) oil paintings, based on memory and photos I’ve taken.

Unfortunately, the results are – so far – uninspired. (I’ll get back to that in a minute.)

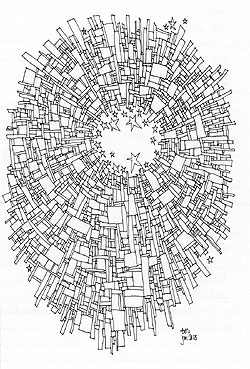

So, I took out my pen and paper, and started doodling one of my Pandorica-inspired pieces. (The Pandorica is a Dr. Who story element.)

I was so caught up in it, I let it run to the edge of the page. And then, I felt so disappointed, because that meant the piece would require an additional, larger support, just to be matted.

This morning, my husband pointed out that it’s a perfectly good work of art, as it is, and there are worse things than needing something in back of the work so it mats well.

He also reminded me that art is about the inspiration.

That gets me back to my paintings… the ones that aren’t turning out.

I said that they aren’t inspired, and I mean exactly that: I’m working on them, production-style. By definition, that’s an industrial approach. (Yes, I am reading Seth Godin’s The Icarus Deception. It’s brilliant, inspiring, and terrifying, all at the same time.)

So, I went back to my Pandorica doodles. I’m waiting for this evening’s sunset, hoping the colors will be inspiring enough to spark (and complete) some or all of the six little paintings currently on my easel.

I want to take them with me to M.I.T. next week, when we’re hearing Seth Godin speak and participating in whatever’s going on at that event. I’d like to hand out art, at random, as a random acts of kindness gesture. In other words, just for fun.

But… I feel a little stuck. And, I’ve been trying to work with a deadline more than inspiration. Bad idea.

It’s compounded by my fear of disapproval, or – worse – no reaction at all. Boredom. Kind of a “What, you think you’re an artist…?” reaction, as they drop the art in the trash. (Have I mentioned how well I can awfulize when I’m in this mode…? *chuckle and sigh*)

Okay. I’m not sure if this is more stage fright or the visual equivalent of writer’s block.

Either way, it’s putting the emphasis on the finished work and others’ opinions – even their potential opinions, if it’s work I haven’t shown anyone – instead of where it belongs, on the inspiration, and the creative expression that results.

But, what I’m describing in angst-laden terms is how we, as artists, make ourselves tiny and insignificant. And, it’s why we often stall and lose precious time in which we might be making art.

It’s a toxic, all-or-nothing approach. It’s so far from being in flow – in the creative process where we’re in touch with the sublime – we couldn’t find it with a road map, a compass, and a laser-tuned GPS.

The teaching…? I’ve become more selective. I decided not to be part of events where profits are more important than the quality of the courses offered to students. (One of my favorite events is still Dragon Con, though you may not think of that as an arts event, per se.)

The art…? That’s another matter. Recovering my willingness to be creative, out loud… that’s why I changed this website back into the blog it was in the first place, back in 1995 or 1996, when I began it.

And, it’s why I’m staring down virtual stage fright, posting last night’s Pandorica piece here, as a graphic and as an ATC you can download (and print at 300 dpi).

Click on the illustration, above and on the left, to print your own copy. Or just click on this link.