Years ago, when I worked in fashion in Los Angeles, a co-worker at the May Company told a great story about a desperate ad campaign. He’d had just a few hours to write a newspaper ad for the ugliest argyle socks ever made. He wrote this headline: “You’ve never seen socks like these!” The socks…

Aisling’s Articles

Collage Art and Assemblage – What’s the Difference?

Collage art and assemblages are just two of the most fun, varied art forms. Even beginners can achieve success with collage and assemblage. The biggest difference between them…? Collages tend to be flat. Or flat-ish. Assemblages can be three-dimensional, and can be small or really, really huge. a collaged card in the Inspiration Deck exchange…

Free ATCs to Print

The following ATCs are free for you to download and print. By the light (R-rated for nudity) – A nude figure and flowers. Dream (R-rated for nudity)- Faerie themed, with a nude in a woodland setting. Everlasting – Eerie image of a little girl with teddy bear. Face behind the words – A mix of…

How to Collage in Your Art Journals – 2008 Art Journaling Update

Collage is an easy way to add art to your diary or journal. For years, I started each day with a quick torn-paper collage, the same as I used to create my handwritten “morning pages,” taught in The Artist’s Way: A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity Collages are a visual version of…

Journaling Your Past – Free eBook

You can write your own life story in just 15 minutes a day. Really. I’m probably best-known for my personal journaling workshops and online art journals. I want to share one of my favorite workshops with you in this free PDF about journaling your own history. Journaling Your Past is a free 26-page manual, and…

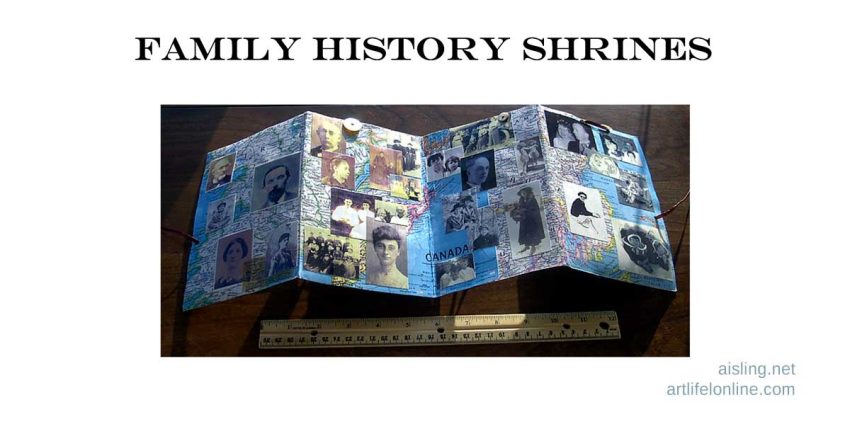

Family history shrines

You can make your own family history shrine or display using this free 14 page PDF. This illustrated ebook includes a supply list, plus step-by-step instructions. It also includes helpful tips for finding family photos, preparing them, and assembling your own family history shrine. In addition, you will find suggestions for teaching this as a…

Planning for your future

This morning, I read Seth Godin’s blog in which he posted a joke set of predictions for 2008. (He claimed to have written them in 2002. Obviously, he’d written them this week.) But, as he concluded his post, he stated his point very well: “…just think about how impossible it is for your to predict…

The importance of leverage

Today, I was reading a blog entry by Rick Sheffren, Leverage: Maximize your income in minimum time. It reminded me of the potential leverage of past accomplishments. As artists, we don’t always pause to update our resumes (CVs). We participate in swaps, group shows, and see our works published in zines and magazines… and all…

Art Consignment for Beginners

Every year, new art galleries and crafts shops open. Often, they’re launched on a shoestring. They need consigned items to sell. Every year, new artists and crafters decide that this is the year they’re going to launch their careers. They need places to show their artwork. It could be a perfect partnership for your artwork…

Recommended: Annual meetings

If you want to meet other artists and talk with them about local resources and outlets for your own art, here’s one great approach: Join art associations and clubs, and — here’s the important part — go to their annual meetings. Unlike some corporate annual meetings, art associations’ meetings can be very sociable and fun. …